In 1962, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, the book that began a huge explosion of modern environmental movements. The huge impacts can be seen in the surge in environmental activism, the rise of ecofeminism, and the creation of government legislation and agencies (such as the EPA) that followed the book’s release. But, often overlooked is the book’s impact on environmental communication.

Environmental communication,as Robert Cox (PhD, University of Pittsburgh) writes, “describes the many ways and the forums in which citizens, corporations, public officials, journalists, and environmental groups raise concerns and attempt to influence the important decisions that affect our planet.”

It is a relatively new field of study, and one we desperately need if we want to better push for change.

It turns out that communication has a lot to do with worldview. In psychology, frames, or schemas, describe typically unconscious structures that people use to understand the world. Frames are important and often activated in everyday life because they help use with a variety of functions, from encoding memory to quickly making judgements about a situation. But because these frames are often unconscious, they are exceedingly difficult to change, even when they are unhelpful. Despite what Enlightenment thinkers believed about the undeniability of facts and the truth, most people do not ever assimilate facts and truth into their pool of knowledge if these facts contradict their frames.

If you saw these two yogurts in the grocery store, which one would you reach for first? The framing effect usually drives us to buy the one on the right (80% fat free), even though both yogurts contain the same amount of fat.

Effective communication, about environment and otherwise, requires being aware of our own frames understanding the frames of those we want to communicate to. Then, it is important to construct arguments that seek to avoid activating an unhelpful schema – once a frame is activated, it helps “shield” the listener from new information. For example, Person A’s frame conceptualizes humans as dominant, conquering beings, while animals and environment are secondary and nonintelligent (and therefore can/should be taken advantage of, as in Manifest Destiny). On the other hand, Person B’s frame may see no such distinction between humans and animals. If Person B wanted to convince Person A that they “should not take advantage of and eat animals, because humans are not a dominant species,” all this would do is remind Person A that they think humans are dominant. However, perhaps phrasing their argument as “should not take advantage of and eat animals, because it is unsustainable and the meat industry has x, y, and z faults,” then Person A would have minimized the opportunity to activate the frame Person B holds about human dominance.

But back to the topic of environmental communication:

Current environment communication, as well as science communication as a whole, relies on an anti-narrative: a narrative that deliberately avoids the typical conventions of the narrative, such as a coherent plot and resolution (thanks, Google). This anti-narrative, clearly demonstrated in the format of a typical scientific article, is used because it helps the writer maintain objectivity, and by extension, authority. Methods, data, and conclusions are clearly outlined, with as little reference as possible to the greater social, political, or economic interests at work in financing or driving the research. But another result of the scientific anti-narrative is exclusion of nonexperts. After navigating through the unnatural presentation of information, the average layman reader must then wade through jargon and highly specialized concepts before understanding the author’s points.

Scientific anti-narrative structure

Traditional narrative plot structure

On the other hand, most are very familiar with the narrative, or the story. Unlike the anti-narrative, typical narratives do form a coherent plot and resolution. In western storytelling tradition*, a plot has 5 main parts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. These parts are usually presented in chronological order, or linearly, to give the audience a clear understanding of how one scene follows from another. To humans, whose very selves/identities are based on self-narratives**, this 5-part plot is incredibly intuitive and easy to understand! In addition, modern storytelling culture and technologies allow for the use of slang, references to other (possibly unrelated) works, highly politically charged sentiments, and memes – all easily digestible by the average person, regardless of any scientific understanding they have.

All this is not to say that we should do away with formal scientific papers (we shouldn’t!), or that we should immediately try to publish stories and scripts about each paper we’ve ever written (our time would probably be better spent elsewhere). But what is important for environmentalists and scientists to do is a) critically review the methods we choose to present our work, and b) learn how to communicate with people who do communicating (novel writers, artists, filmmakers, game developers, etc.). So, below I give some guidelines that scientists can use to draft a story or understand the benefits of some visual media.

The Environmental Communication journal, published by the International Environmental Communication Association (IECA) includes research on the use of communication strategies in various fields of environmental study.

Science Through Story provides training and resources for scientists to learn how to share their work through storytelling. Workshops are hosted by Sara Elshafie, a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley.

Once a scientist decides to use a narrative to share their findings, how can they communicate to a storyteller or artist what they envision?

A good place to start is to create a compelling*** narrative pitch. To do so, it is often helpful not to begin grandiose idea about the impacts of global climate change on all the countries around the world. It may be better to begin smaller: with characters and conflicts. Who is the character, and what do they want? What stops the character from achieving their goals? Once some ideas come to mind, it might be time to use a story spline to get a basic structure.

The Pixar Story Spline. Notice that this spline uses “And because of that…” instead of “And then…” — the events of your story should feel as though the logically follow from one to another.

With this exercise, one can often find that the story goes “off-track” and diverges from the original intended storyline dedicated to environmental issues. And that is ok! Some of the best representations of environmental issues I have seen were not about environment at all (such as the film Parasite). Compelling characters, environments, and plots are creative endeavors, and all creative endeavors take time.

Once the plot is established (or even before), it is important to decide what medium to tell the story with. Stories can be presented in words, in images, in a game, in film, etc. Once created, they can be disseminated on social media, in a movie theater, online, through published books, etc. Each medium has its own strengths and weaknesses and its own level of accessibility. Because I have spent most of my time at Berkeley engaging in using visual media, I will focus on giving some thoughts about them.

Visual media can be a great tool to use to tell stories about the environment. Often, words and jargon alone can exclude non-specialists and be confusing or difficult to navigate. Visuals such as graphs, charts, or diagrams can often help make sense of information and data. And, arguably most importantly, people love to consume visual media! From paintings to movies to video games, visual media are highly popular ways for people to either relax or interact with each other.

Here are overviews of three of my favorite types of visual media:

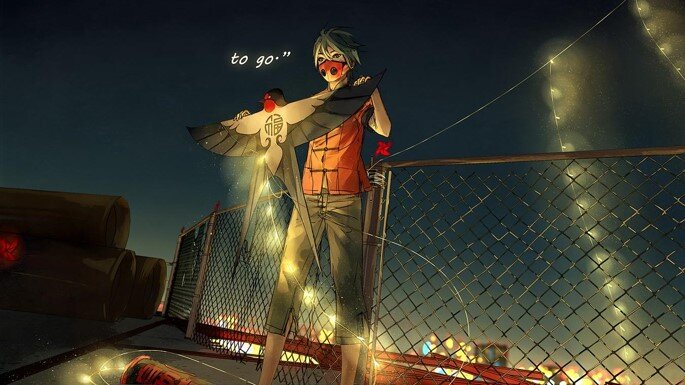

1. Images/comics: to create a still image, artists (and photographers) often begin by considering composition – literally framing the way we are viewing the image. This is a great opportunity for the artist to implicitly draw on certain frames we have as gazers of a scene! Still images also have to rely on icons and symbols for storytelling. Sometimes, these symbols can be used to great effect to draw the viewer’s attention to interesting plays on iconography or challenge the viewer’s beliefs (Banksy graffiti is a great example of symbol play). And, when communicating story, let’s not forget the importance of character design. Characters drive stories – so when we bring them to life visually, we need to consider how they are perceived at first glance****. The clothes that a character wears, the shapes that make up the character’s silhouette, and even the colors used in the character’s outfit are all consciously made decisions that are meant to help the viewer understand quickly and effectively.

An illustration by Wenqing Yan. Notice how symbols of grassroots activism and protest, the spray paint and gas mask, are combined with symbols of nature, suggesting that environmental advocacy is rebellious.

An example of an icon found in green movements. Often, such icons depict the earth, to suggest global unity. But, such iconography can lead people to overlook inequities between different parts of the world. Being careful about these iconographic choices is important!

A panel of Wenqing Yan’s comic, Knite. Here, the framing of the characters relative to a smoggy city suggests their powerlessness.

A panel of Wenqing Yan’s comic, Knite. Here, the framing of the character relative to the background suggests that the character is powerful and in charge.

Example of character designs from the Pixar move, Up.

2. Animations: to create an animation, an animator (or more often, group of animators) put together several still images to create the illusion that the images are actually moving. Animators need to consider many of the same things as illustrators or artists (such as composition, colors, lighting, and the use of icons). Now, we add in the dimension of time: how do the character, setting, and themes change over the course of a scene? An entire film? Character-specific movements can sell the character’s personality or relatability. In addition, with today’s 3D animation technology, we can create and render 3D simulations of change over time, which is important for visualizing how global change processes might alter landscapes. These animations (as well as the still frames that go into them) are useful tools for students of physical processes or anatomy to visualize the contents of their study. On the flip side, animators, pursuing realism and appeal, often need to ask a well-researched scientist about anatomy or growth patterns to create better animations for their audiences. Communication between scientists and animators is already happening, but what if this communication also involved the storytelling behind an animation? I think that there is great potential for great stories here.

An example of an animator’s breakdown of a bull’s walk cycle. Animators need to study from reference to obtain the “right” look - sometimes, they need to ask a professional or a scientist.

Once scientists have information, they can work with animators to create educational visualizations.

An amazing film by animation students at GOBELINS. Notice how the characters and setting change over time.

3. Video Games: to create a video game, a game developer has to think now about immersion and interactivity. Video games, unlike the first two media, are very inherently user-based. The developer creates the game, but it is the player who makes choices about where to go, what to do, or even who to play as. This is a unique opportunity for the creator to hold a conversation with the player, even without the creator present. A video game developer can implement features that change over time, or a set of difficult choices for the player to make, or simply create an open-world, unguided adventure – and when the player makes their choice about what to do, the changing world or dialogue options in a game speaks for the developer. Video games are also very effective educational tools. By providing a space where a player could role-play a situation that is impossible to implement in real life, video games can encourage exploration of a variety of different choices and their consequences, providing first-hand experience for the player.

“Plasticity is a cinematic platformer about a young girl named Noa, who explores and decides the future of her post-oil, plastic-ridden world. Players will make choices that either help or harm the environment, and see how the decisions they make shape their journey and alter the future.”

Journey (2012) is an open-world game where characters explore a beautiful world on their own or with friends. While not necessarily environmentally-related, this game elevates the aesthetic value of the environment.

Undertale (2015) is an incredibly meta video game that challenges the player’s frames about killing characters in video games. While not necessarily environmentally-related, this game may be a useful reference for game developers who want to challenge a player’s frames about eco narratives.

In conclusion…

…environment communication has traditionally taken the form of scientific research papers (and the occasional book or two), but new medias and technologies allows for new and innovative methods of communication. As scientists, it is our job to find the truth. As environmentalists, it is our job to spread the word and incite the change we want to see. And to do this, it is important to make use of these forms of communication and creatively find ways to bring our stories to life. By working together with experienced storytellers, artists, or game developers, environment scientists can hope to bring their research to the forefront of public consciousness in a way that is enjoyable and engaging for their audience.

Some notes:

* In this blog, I discuss western storytelling tradition, which tends to focus on a more linear, conflict-driven plot and a singular main character. This is as opposed to eastern storytelling tradition, which tends to focus on emotions and many main characters. Neither tradition is better than the other, but trying to tell one style of story in the culture of another may lead to criticism or misunderstanding. I have personally experienced a case of this while working on an animation for CNM 190: Advanced Digital Animation.

** Knowledge taken from CogSci 180: Mind, Brain, and Identity, taught by Prof. Ben Pageler.

*** Compelling doesn’t necessarily mean beautiful or aesthetically pleasing. Here, compelling refers to a story/character/setting/action/movement/etc. that is believable and relatable. A villain can (and should!) be a compelling character. A tragedy can be a compelling story, but with the context around environment narratives being oversaturated with tragic ones, it might not be the best type of story to tell your audience (if you can help it).

**** Quite unfortunately, character design as an art and field of study is completely based on appearances and first judgements. For example, round shapes are friendly and soft, so characters that are friendly often use round shapes. On the other hand, jagged shapes are scary and dangerous, so characters that are scary or villainous often use sharp, pointy shapes. The line that separates shape language from stereotyping can be pretty thin, or maybe not a line at all. Pursuing this topic further is probably a worthwhile task.

Sources:

Lakoff, G. (2010) Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environmental Communication, 4, 70–81.

Lindenfeld, L.A., Hall, D.M., Mcgreavy, B., Silka, L. & Hart, D. (2012) Creating a Place for Environmental Communication Research in Sustainability Science. Environmental Communication, 6, 23–43.

Padian, K. (2018) Narrative and “Anti-narrative” in Science: How Scientists Tell Stories, and Don’t. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 58, 4, 1224–1234,

Pezzullo, P.C. & Cox, J.R. (2018) Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Pixar in a Box: The art of storytelling. Khan Academy. URL https://www.khanacademy.org/partner-content/pixar/storytelling

Rega, E. (2018) Visual Narrative and Jargon Minimization Underpin Anatomy Teaching to Animation/VFX Industry Professionals and Health Professions Students. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 58, 1255–1268.

The IECA. (2020) URL http://theieca.org/

Tips From Disney (TFD). (2015). D23 Expo 2015 Gets Turned “Inside Out”. URL http://www.tipsfromthedisneydiva.com/d23-expo-2015-gets-turned-inside-out/

Yan, W. Yuumei Art. URL https://www.yuumeiart.com/